About

About

Our Mission

- Promote lifelong wellness through continuous and progressive physical and mental development for all nationalities, with special emphasis on the youth including People of Determination.

- Recognize, appreciate and maintain the “rich heritage” and legacy of Hanthawaddy Burmese Bando as designed by the masters of the past, and as introduced in the United States by Dr. U Maung Gyi, Grandmaster and Founder of the American Bando Association (ABA).

- Contribute to the positive social, economic, leadership and educational development of the United Arab Emirates, to include-but not limited- to promoting an anti-terrorism, crime-free, and drug-free society.

VISION

Promote the principles, philosophy and practical applications of Emirates Bando as a means of improving the lives of people in the United Arab Emirates and the region

GOALS

Provide the most effective martial arts program in the region. Help to build the Islamic characters of the youth in the region.

Character Building Initiatives

About

Our motto is: “Developing the best character is our focus”. Hence, we would like to clearly convey to all parents and students that Bando is not just about fighting. It’s a sport like any other sport… tennis, football or cricket. And like all other sports, Bando is a tool to stay physically fit, an education about eating and drinking nutritional things, maintaining wellness, and living healthy lifestyles. However, in terms of personal values and competencies it helps students to learn discipline, improves their confidence about themselves, enhances their ability to follow instructions, teaches them how to effectively work with culturally diverse students, how to function in an organized and structured environment….. among other things. So it’s not about how well the student can fight, but it’s about the character that the fighter will build over time to become a smart boy, talented young man, and eventually a responsible adult that will make significantly positive contributions to his family, the community, and the progressive growth and development of the UAE overall.

To help the students achieve these broad aims, we have incorporated 11 Character Building Initiatives (CBI) within our Bando program. We hope that these initiatives will have a positive effect on their behavior. We want to help them become more responsible now so they can continue to become responsible adults in the future. Through Bando we can all help to achieve this vision.

Based on the above, the objectives of the CBI are listed below:

- Energy Conservation

- Crime Prevention

- Digital Technology

- Health & Nutrition

- Young Entrepreneurs

- Academic Excellence

- U.A.E First

- Community Volunteerism

- Creative Thinking

- Problem Solving

- Emotional Intelligence

About BANDO

About

What is Bando?

Generally, the term “Bando” means:

- The Way of Disciplined Warrior

- A System of Self-Defense

- The Art of Empty-hand Fighting or Combat

The word “BANDO” (pronounced “Bawn-Do”) is a multi-faceted martial art system, with roots in China, Burma, and India. Various etymologists express their views toward the word differently. Some say that it originated from the Chinese, while others claim that it came from India, and then there are those who propose that it can be traced back to Tibet.

The word “Bando” has been used in place of the concept of “THAING” or “BAMA THAING” for easy pronunciation and identification. The word BANDO is easily pronounced similar to the words Budo, Judo, Aikido, Karate-do, Tae Kwon Do, etc.

There are also numerous interpretations of the term “Bando”. Different linguistic and ethnic groups define and interpret the word differently, and often some Bando schools emphasize only one aspect of the Bando Discipline, such as that of an empty-hand system.

Bando is not Karate. The karate-like techniques of striking, kicking and butting are but a few of the aspects of the Free Hand Weapon of the Bando Discipline. Other aspects of the Free Hand Weapon of the Bando Discipline include grappling techniques of throws, trips, flips, holds, locks and chokes. In Myanmar [Burma], the Free Hand Weapon is traditionally called “Bando”. Additionally, there are the aspects of the other Weapon Hands of the Bando Discipline- traditionally called “Banshay”, such as stick fighting, sword fighting, knife fighting, spear fighting, gun fighting and combat archery. Both traditional “Bando” and “Banshay” are combined for our purposes into the Bando Discipline.

The Bando system is defined as the following subsystems:

- DHOE (empty hand) – Lethway (Kick-boxing), Free-fighting

- DHOT (stick hand) – Dhot Shay (long staff), Pongyi Dhot (medium Staff}, and Dhot Lay (short stick

- DHA (sword hand – Min Dha (long sword), Kukri (medium sword), and Dagger (short sword)

Traditionally, Bando students are encouraged to learn and develop knowledge and skill in at least 3 areas, one from each subsystem. Instructors strongly encourage their students to attend National Bando clinics and seminars to expand their knowledge on the different sub-systems of Bando. Studying only one sub-system is inadequate and restrictive.

As the old Bando saying goes, “One Finger Does Not Make the Fist.”

*********

“As no one nation or people have the monopoly of the sunlight.

No one system, school or doctrine has the monopoly of the TRUTH”.

– Bando Motto

About

History of Bando

Dr. Maung Gyi’s father, Sayaji U Ba Than Gyi, became a key part of the post-war Burmese government. A brilliant scholar and masterful martial artist, U Ba Than Gyi had played a key role in the establishment of the Military Athletic Club in pre-World War II Burma. Now, he would find himself in an ideal situation to further the goals of the Military Athletic Club: U Ba Than Gyi would become the director of the Burmese program of physical education and athletics. To Bando’s great benefit, U Ba Than Gyi seized the opportunity to travel throughout the country under the auspices of the government. He sought out masters of the martial arts throughout Burma from many styles and systems.

By the end of the 1940s and the early 1950s, U Ba Than Gyi’s efforts had begun to flower. He had systematized a number of approaches into a distilled and internally consistent style called “Hanthawaddy Bando”. This system is by no means all of Bando or all of Burmese martial arts. It is, as Dr. Gyi calls it, a piece of the larger puzzle.

About

Resurgence of Bando Boxing

As he undertook to gain widespread credibility and acceptance across stylistic, racial/ethnic and class lines, U Ba Than organized the traditionally brutal and savage indigenous Bando Boxing, in an attempt to make it safer and to reduce injuries and fatalities. At that time in the early post-World War II period, Bando Boxing was not yet “Westernized”. The Thais, however, proved less resistant to change and fairly readily westernized Muay Thai.

U Ba Than Gyi’s son, Maung Gyi (Dr. M. Gyi), was a participant in these bouts. These brutal experiences made an indelible impression on Dr. Gyi. To this day, he insists that Bando be highly effective in combat.

Reviving Bando Boxing was a critical way to establish credibility for U Ba Than Gyi with the “underground” martial arts culture. His involvement in the Military Athletic Club and his force of personality all combined to uniquely qualify U Ba Than Gyi as the man who could elicit the essence of the underground systems from the remaining masters.

One enormous problem facing U Ba Than Gyi was the difficulty encountered in resurrecting and reviving systems without offending the holders of the knowledge. A keen political balancing act was needed to satisfy the demands of surviving “traditional” masters, heads of family systems, various monk sects and ethnic groups. Thus, as U Ba Than traveled the country and contacted a growing network of such persons, he interviewed them and gained their confidence gradually.

As he began to perceive the nature of what had been driven underground, U Ba Than Gyi concluded that a real part of the Burmese culture had been threatened with extinction. In Burma, the martial artist lived as a critical part of the society. Not only could one punch and kick, but was a kind of “Renaissance Man” or “Renaissance Woman”.

The Burmese martial artist was, traditionally, in addition to being a repository of knowledge concerning methods of harming or killing the individual, a repository of knowledge concerning health and healing. Frequently, martial artists were indigenous medical practitioners to whom the community turned for treatment from illness and injury. Moreover, the martial artist in Burmese society was sought after by the populace for his or her understanding of nature, animals, plants, the elements, geography, language and customs, as well as historical fact and cultural traditions. Frequently, because of their advantages in these areas, they were called upon to act as arbitrators of disputes, or as judges. Thus, the Burmese martial artist, prior to the British suppression of the arts, had served in a highly respected position in the society. Therefore, the presence of the martial artist in a community or in a given situation, was the presence of a person of wisdom (a physician, herbologist, scholar, warrior, philosopher, jurist) and was the symbolic infusion of great power and justice into a community environment or an inter-personal or inter-group transaction.

Recognizing this, U Ba Than Gyi gave these surviving masters the deference they deserved, and asked that they share with him, for posterity, their knowledge. The reaction to Gyi’s shrewd and genuine inquiries was outstanding; some 200 masters met with him, taught him and demonstrated their methods, disclosing the history and context of their heritage.

The British had originally suppressed the native Burmese martial arts, as had been the case with the rulers of Okinawa. And, as was the case in Okinawa, the indigenous Burmese martial arts had not disappeared altogether. Instead, masters and families had kept the suppressed systems alive in secret. Now, Sayaji U Ba Than could travel the nation openly and confer with these living legacies.

U Ba Than was particularly interested in organizing the knowledge of the surviving masters in Burma. Their arts had been preserved within close-knit family structures, or perhaps disguised for preservation in the form of folk dance (as in China and Okinawa), or in forms of entertainment, such as the theater and the opera, as in the Chinese opera. In addition, some clever progenitors had hidden the essence of some systems in the guise of sports activities, channeling aggression and conflict into an arena between two men as opposed to training groups to undertake resistance against the government.

Eventually, martial artists from many styles came to visit the Elder Gyi’s (U Ba Than Gyi’s) compound and demonstrate their various systems. Those demonstrations were very demanding. “Masters” who could not perform on their promises faced a series of aggressive “reality checks”. For example, Dr. Gyi relates the story of one “master” who claimed his martial prowess would allow him to defeat ten attackers simultaneously. A test was arranged at a soccer field by the Elder Gyi. Ten attackers were arrayed against the “master”. The “master” was simultaneously attacked by all ten.

The Common Thread: “Principles”

As he pursued the laborious process of systematizing this huge body of evolved knowledge, U Ba Than began to realize that, despite varied origins, purposes, outward manifestations and historical contexts, all martial systems shared, at their root, certain immutable and common principles. He also noted that there was an inevitable overlap between related (but not identical) systems.

For example, the Cobra and Viper shared many similarities, as did the various cat systems, such as Black Panther and Tiger. It was just this sort of organization of previously disconnected and inchoate knowledge that was U Ba Than Gyi’s great contribution, achievement and breakthrough. U Ba Than asked this question: How do we share this knowledge with other interested individuals in a limited time? Many of the systems included as an integral part of their existence a rich and complex body of legend, myth, religious practice and encrusted tradition. These qualities required years, even a lifetime of study in order to assimilate the system.

As he engaged in cultural archaeology, restoration and preservation of the Burmese martial arts culture, the impossible task facing U Ba Than Gyi was this: how do you test the validity of the myth? He began to sort out family legends, stories, myths and traditions which could not be verified, and began to reduce his information to a system of principles. He left his son volumes of encrypted notes on the systems and principles he unearthed.

Hanthawaddy Bando: A Summary

By the end of the 1940s and the early 1950s, U Ba Than Gyi’s efforts had begun to flower. He had systematized a number of approaches into a distilled and internally consistent style called “Hanthawaddy Bando”. This system is by no means all of Bando or all of Burmese martial arts. It is, as Dr. Gyi calls it, a piece of the larger puzzle.

- 1957– Started teaching Bando [ancient martial arts system from Burma] at the Burmese Embassy in Washington, D.C.

- 1960– Taught Bando as a sport in the physical education program at the American University in Washington, D.C.

- 1964 – 66– Worked with GM Jhoon Rhee, [considered to be the Father of American Tae Kwon Do], promoting National Karate Championships in Washington, D.C.

- 1964 – 70 – Worked with GMEd Parker {founder of American Kenpo System} at the USKA and other national championships held in Florida, Chicago, Washington, D.C. and New York.

- 1964 – 72– Worked with GM Ki Wang Kim {Founder of Korean Tang Soo Do Association} judging and refereeing Korean sponsored tournaments in the East Coast region.

- 1964 – 76– Worked closely with GM Robert Trias, [founder of United States Karate Association, USKA], promoting and organizing major national and world karate tournaments

- 1966– Moved to Ohio University to pursue a D. program in psychology, language and communication; and worked with GM Harry Smith [one of the pioneers in Ishinryu karate] in Pittsburg, Pennsylvania

- 1966 – 70– Worked with GM Peter Urban, {founder of American Goju Ryu} at major East Coast Karate Championships.

- 1968– Formed the American Bando Association [ABA] as a Private, Non-profit Veterans Memorial Martial Arts Organization to pay special tribute to both the Allied and Axis troops who fought and died in the Burma Campaign during World War II. The first Induction of Full Members into the ABA occurred in Athens, Ohio. Later, the ABA was formally incorporated as a non-profit corporation in 1986.

- Appointed as the Chief Instructor of theUnited States Karate Association [USKA then was the largest martial arts organization in the US.]

- Received Special Citation from GMTatsuo Shimabuku, [founder of World Okinawan Ishinryu Karate Association]

- Conducted seminars with GMHarold Long [one of the pioneers of Ishinryu karate in the South] in Chattanooga, Tennessee;

- Worked with GMDon Nagle {one of the pioneers of Ishinryu Karate of the East Coast} in NY.

- Appointed byThe Black Belt Magazine to serve as Chairman of The Rules and Regulations Committee to provide guidelines to all major Karate tournaments in the United States and Europe.

- Promoted theNational Bando Free Fighting Championships in the USA

- IntroducedBando Kickboxing Championships in the USA.

- 1968-70– Conducted seminars with GM Don Bohan and GM Rick Niemira {pioneers of Ishinryu Karate in MD.}

- 1968-71 –Worked with GM Mas Oyama {Founder of World Kyokoshinkai Association} at North American karate tournaments, served as Chief Referee.

- 1976 –Appointed as the Chief Referee for the Professional Karate Association {PKA} by Don Quine and GM Joe Corley.

- Appointed as the Chief Referee for theWorld Professional Karate Championships by GM Aaron Banks

- 1985 –Appointed as Visiting Scholar at Harvard University {Dept. of Psychology}

- Conducted Seminars with GM GuruDanny Inosanto at the Inosanto Martial Arts Academy in Marina Del Rey, California – {to Present}

- Worked with GMFred Degerberg at the Degerberg Martial Arts Academy in Chicago {to Present}

- 1986 –Appointed as Visiting Fellow at the John Hopkins University {Dept. of Psychology}

- 1990 –Served as Senior Mentor to GM Zufi Ahmed {founder of Bushi-Ban International Organization} in Houston, Texas – {to Present}

- 1995 –Retired as Associate Professor from the College of Communications, after more than 30years of teaching at Ohio University.

- 1999 –Conducted seminars with GM Remy Presis {founder of Modern Arnis, Filipino stick fighting systems} in Buffalo, NY.

- 2000 –Conducted Seminars with Guru Marc Denny {Dog Brothers Martial Arts} Hermosa Beach, CA

- Conducted seminars withTim Hartman {founder of World Modern Arnis Alliance} in Seneca, NY {to present}

- Conducted Seminars with GMJoe Palanzo {President of the World Wide Kenpo Karate Association, WKKA} Annual conferences, Baltimore, Md. & Connecticut {to Present}

- Served as Senior Mentor toJoe Lewis Fighting Systems and conducted seminars at the annual conferences in Florida {to Present}

- Served as Senior Mentor of GMDennis Tosten {President of Ameri-Kick Martial Arts Organization} in Pennsylvania {to Present}

- 2005 –Honored by the Ambassador from Myanmar (Burma), U Linn Myaing, for contributions to the martial arts community in the USA

- Moved toPeachtree City, GA with his wife, Patricia. He continues to translate and write articles for the ABA; he runs seminars on the ancient healing arts of Tibet, India, China and Burma; he teaches the Bando Monk System to interested persons twice a week at his home; he practices meditation and Dhanda Yoga, Longi Yoga and Letha Yoga to maintain his health and flexibility.

Throughout the late 60’s, 70’s and into the early 80’s, Dr. Gyi worked with GM Don Nagle [one the pioneers of Ishinryu karate on the East Coast] in New York; worked with GM Ed Parker [founder of American Kenpo System] at the USKA and other national championships held in Florida, Chicago, Washington, D.C. and New York; worked with Grandmaster Ki Wang Kim [founder of Korean Tang Soo Do Association] judging and refereeing Korean sponsored tournaments in the East Coast region; worked with Grandmaster Peter Urban, [founder of American Goju Ryu] at major East Coast karate championships; conducted seminars with GM Don Bohan and GM Rick Niemira [pioneers of Ishinryu karate in the East Coast] in Maryland; and worked with Grandmaster Mas Oyama [Founder of World Kyokoshinkai Association] at North American karate tournaments and served as Chief Referee.

In addition, Dr. Gyi was appointed by The Black Belt Magazine to serve as Chairman of The Rules and Regulations Committee to provide guidelines to all major karate tournaments in the United States and Europe; promoted the National Bando Free Fighting Championships in the US; introduced Bando Kick-Boxing Championships in the U.S.; was appointed as the Chief Referee for the Professional Karate Association [PKA] by Don Quine and Grandmaster Joe Corley; and was appointed by Grandmaster Aaron Banks as the Chief Referee for the World Professional Karate Championships.

As an academic educator, Dr. Gyi was appointed as Visiting Scholar at Harvard University [Department of Psychology] and as Visiting Fellow at the John Hopkins University [Department of Psychology]. Dr. Gyi retired as Associate Professor from the College of Communication, after more than 30 years of teaching at Ohio University in Athens, OH. In addition to his academic work as a professor and teaching Bando, Dr. Gyi coached the Ohio University Boxing Team. For 25 years, his boxers successfully competed in the Midwest Regional Collegiate Boxing Championships, the National Collegiate Boxing Championships, the U.S. Military Academy, U.S. Naval Academy, U.S. Air Force Academy, Virginia Military Academy, U.S. Marine Corps and other institutions such as Notre Dame University, University of Michigan, Villanova, etc.

1985 – 2005 – Dr. Gyi’s Kukri [Sword] Drill Teams performed at the annual reunions of:

- National Burma Star Veterans Organization

- China-Burma-India Veterans Organization

- S. Merrill’s Marauders Veterans Organization

- S. 1st Air Commandos Veterans Organization

- National Flying Tigers Veterans Reunions

- National US Air Commandos Veterans Reunions

- S. OSS 101 Veterans Organization and other WWII veterans organizations

Instructor's Bio

About

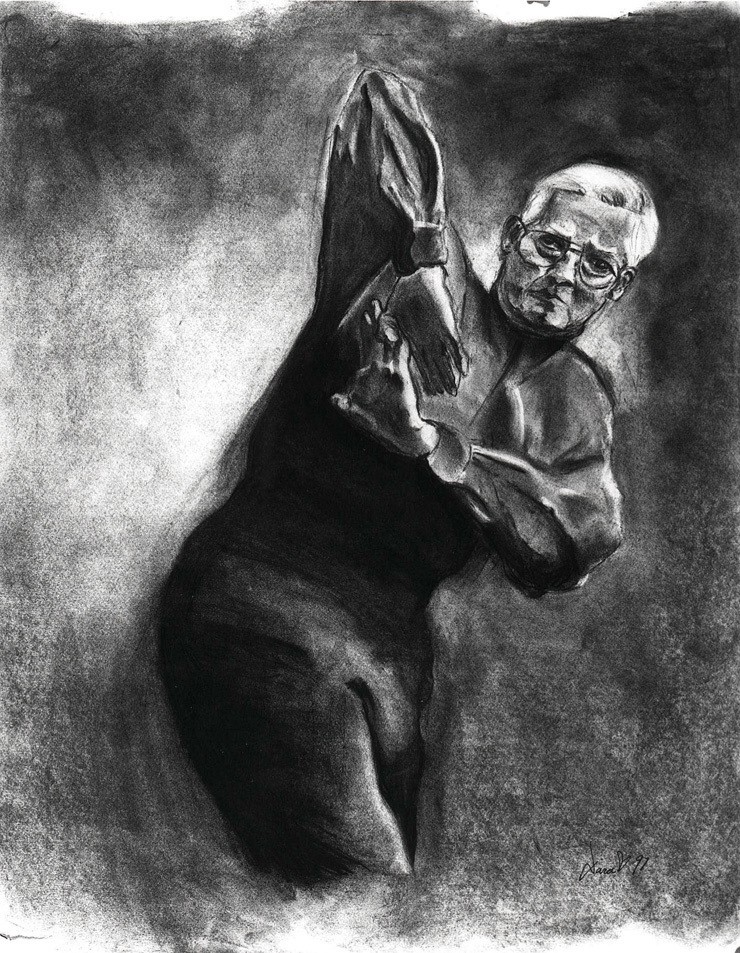

Dr. Maung Gyi

Terms like ‘legendary,’ ‘brilliant,’ and ‘genius’ are frequently used in popular culture to describe individuals who have distinguished themselves in some way. These descriptors are often misapplied to persons who have exceeded mediocrity, yet who have not reached the point of true exceptionality. Such superlatives are, however, appropriate when qualifying the lifelong accomplishments of Dr. Maung Gyi, whose innovations, intellect, and influences make him the exception that defines the rule.

Consider, for a moment, the fact that Maung Gyi changed the martial arts landscape of America nearly 50 years ago. He introduced his unique Burmese combat system, known as Bando, to the U.S. in the late 1950s–a system replete with striking methods, grappling strategies, weapons techniques, and so much more. The broad community of martial artists continue to pursue the knowledge he possesses decades after his early groundbreaking exploits.

Why is this? The answer can be found in Dr, Gyi’s own journey toward self actualization and personal enlightenment. His quest for knowledge has never ceased, nor has his pursuit of excellence in martial arts performance.

The elder Gyi—whose military name was Bawanje Rai—served as an officer of the 10th Burma Gurkha Rifles, and was formally educated in linguistics and physiology. Ba Than Gyi formed the Military Athletics Club in Maymaya, Burma during the mid 1900s, with the support of colleagues from the Burmese military.2 He was successful in efforts to restore and modernize the ancient fighting systems endemic to the region, including systems from India, Tibet, and China. Although elder Gyi’s initiatives were driven by a strong cultural imperative, the spread of global conflict during the late1930s and early1940s significantly influenced Bando’s development.

Gyi the ‘Warrior’

In the early 1940s, young Maung Gyi faced extreme disappointment as his dreams of becoming a physician faded. Political conflicts between his native Burma and the imperialistic Japanese leadership led to a war between the two nations. All adult males in the Gyi family joined the Burmese military during World War II, and there were casualties among them. Uncles, cousins, and even Maung Gyi’s brother were killed in battle.

Recruited to serve in a Gurkha regiment, the youthful Gyi spent some of his military service as a medic, which continued to fuel his ambitions for a medical career. However, his fate shifted dramatically as Maung Gyi was forced to defend himself against Japanese soldiers, while attempting to aid fallen comrades on the battlefield. During this phase of life, Maung Gyi benefitted directly from his father’s insights regarding the applicability of Bando techniques. With khukuri in hand, he fought in dark trenches, jungle thickets, and hilly terrains against armed opponents. The rule was ‘kill or be killed,’ and Gyi chose survival.

The Japanese were armed with katanas (e.g., long swords ) and bayonets, while the Burmese soldiers used their short-bladed swords (e.g., khukuris) to fend off the foreign invaders. The young Maung Gyi had received instruction on combat uses of the khukuri during military basic training. He honed his sword skills on the battlefield and developed a keen sensibility for ‘pragmatics’ in the martial arts. Daggers, swords, long staffs, and other handheld weapons were used in battle by Gyi during the Japanese incursion. The need to survive forced him to learn combat techniques quickly and efficiently. British military historians and achievers have, in fact, credited Maung Gyi with several battlefield kills during World War II.

The ‘enlightened journey’ of Maung Gyi continued in the years immediately following World War II, where he benefitted directly from his father’s insights on fighting systems. Still in his early 20s, Gyi worked closely with his father and other combat veterans to document various elements of the Bando system. Careful attention was given to integrating higher-order skills into a comprehensive fighting system that would reflect both the vision of Ba Than Gyi and the diverse martial techniques of the Burmese region–particularly the animal fighting styles.3 Principles and practices learned from martial-arts masters were carefully recorded and organized into an evolved Bando system.

The Enlightened Journey of Dr. M. Gyi—Page 4

The elder Gyi, Ba Than, invited martial-arts masters from China, India, and Tibet to share their fighting techniques and strategies with the Burmese. Maung Gyi, aided by two other young scholars, was given responsibility for studying and documenting the various styles presented by the foreign masters. Techniques for edge weapons and staffs were presented by Chinese practitioners, while Indian masters share highly effective grappling methods. Animal fighting systems from Tibet and southern China were also prominently explored during these post-war years. Ba Than Gyi carefully guided this development process, ensuring that only functional elements from these diverse approaches would be incorporated into a modernized Bando system. His military background and recent war experiences ensured that Bando would remain a practical system. Nevertheless, the elder Gyi held firm to a philosophy that “...no one system has a monopoly on truth...” This axiom continues to influence Bando’s evolution, even in the twenty-first century.

While Maung Gyi was influenced by each fighting approach to which he was exposed, there grew within him a profound interest in the Cobra Style. He actually spent an extended period living with a Cobra master who raised these animals for their venom. Maung Gyi would subsequently become a Cobra master himself and teach the system to others. Unable to ignore the warrior spirit within, Maung Gyi also delved deeply into techniques of the Bull and Boar Styles, effectively integrating certain techniques into the sport of Bama Lethway (i.e., Burmese kickboxing). He competed in dozens of matches against fighters throughout Southeast Asia, including Thailand, Laos, and Malaysia. Eventually, the youthful Gyi became a champion fighter and gained international recognition for his skill.

Maung Gyi’s ‘enlightened journey’ continued, as he moved to the United States in the late 1950s. His primary purposes for relocating were to pursue higher education and to support the humanitarian efforts of his uncle, the late U Thant, who served as Secretary-General of the United Nations from 1962-1971. While employment and educational opportunities attracted Maung Gyi to the states, advancement of the Bando system may well have been the compelling force that kept him in America.

Shifting his energy away from survival and competition, Maung Gyi enrolled in several prestigious institutions–including Johns Hopkins and Harvard Universities–subsequently attaining both law and doctoral degrees. While working as a linguist in Washington, D.C., Gyi introduced a modified version of the Bando system to a few select students in 1960. He also trained secret service personnel, FBI staff, and security officials during this phase. A few years later, he organized the first Bando club in the states at the American University in D.C. Many students were attracted to Bando because of the uniqueness of this Burma-based fighting style, which preceded other Southeast Asian arts in the U.S. by decades. Techniques of the Bando system contrasted sharply with those of the popular Japanese and Korean styles that dominated the martial-arts scene. Practitioners were impressed with the speed and efficiency of Gyi’s techniques.

Throughout the Eastern Seaboard, Gyi entered his students into karate tournaments and forms competitions. These early students, clad in non-traditional black uniforms, dominated their matches and captured many titles. Shin kicks, leaping punches, and knee blocks were nearly unknown outside of Bando, and Gyi’s early students applied these techniques effectively against other stylists. Word of the system’s effectiveness spread throughout the martial-arts community, causing some otherwise successful practitioners to avoid tournaments where Bando students were entered. Lloyd Davis, Joe Manley, Bob Maxwell, Carl Beamon, Mfundishi Maasi, and Rusty Gage were respected names at karate tournaments, and they helped to foster Bando’s growing reputation.

Having mastered the Cobra Style, Maung Gyi was periodically invited to offer public demonstrations of the rarely-seen animal system. A primary offensive technique of this animal style is the ‘cobra strike,’ which simulates a cobra’s venomous bite against its prey. To illustrate the effectiveness of this type of strike, Gyi had an assistant toss several inflated balloons into the air. In rapid succession, Gyi struck the free-falling balloons with a single cobra strike, causing them to burst. His hands moved with such speed that the actual strikes could not be seen. It gave the ‘illusion’ that the balloons were bursting on their own. Observers of the demonstration were mesmerized, almost incapable of processing what they were witnessing. Such demonstrations fostered the mystique of Maung Gyi and his art of Bando–a mystique that continues to this day.

(kenpo), Mas Oyama (kyokushinkai), Harold Long (isshin-ryu), Robert Tias (shorin-ryi), Mas Oshima (shotokan) and Jhoon Rhee (taekwondo). These early accomplishments of Maung Gyi were a testament to his skill and intellect. He served as ‘chief referee’ for most major karate tournaments throughout the country, and chaired the Tournament Rules Committee for Black Belt Magazine, which established a point system for karate matches. Many of the early karate matches refereed by Gyi involved noted champions, including Mike Stone, Chuck Norris, Bill Wallace, Joe Lewis, and Tom LaPuppet.6

With over 90 Lethway and Tai-Boxing matches to his credit from the formative years in Burma, Maung Gyi introduced the sport of kickboxing to the U.S. He organized the first full-contact Bando Boxing match in Washington, D.C. during 1960, and formed the American Bando Association (ABA) to foster ancient Burmese fighting systems and to support military veterans. The innovations made by incorporating Western boxing methods into traditional martial arts were nothing short of ‘mystical.’ As an Olympic finalist in boxing, Maung Gyi was well aware of how Western boxing techniques could radically augment and improve Bando and other Asian fighting systems.

Gyi competed successfully in professional boxing matches in New York and New Jersey, periodically knocking out heavyweight opponents. What is most impressive about these matches is the weight differential. Maung Gyi weighed between 140 and 145 pounds at the time and only fought against light-heavyweight and heavyweight opponents.

Gyi the ‘Monk’

With a beautiful wife by his side, Maung Gyi sought new vistas in the college town of Athens, Ohio during the 1970s. This rustic setting offered many attractive features to the combat veteran whom found himself drifting further away from the sorrow and pain of Burmese battlefields. Good schools and wholesome social options in Athens proved ideal for rearing his two children–Malinda and Serena. Both Maung Gyi and his wife, Patricia, found the intellectual environment of Ohio University suitable for professional growth and career development. After completing additional graduate training, Dr. Gyi joined the university faculty and distinguished himself as a psycholinguist in the School of Communications. Mrs. Gyi, too, completed graduate training at Ohio University and served as an administrator in the College of Medicine. Even the Gyi children found academic success in the quaint college town through advanced placement courses and attainment of an undergraduate degree.

Maung Gyi’s biological family flourished in the fertile grounds of Athens, and there was comparable growth in his Bando family, as well. The hills and forests in the region created an exceptional training environment for Bando practitioners. Gyi was able to capture and share the rugged Gurkha discipline with his students during seminars and camps. Running, crawling, climbing, swimming, and hiking were all requirements for advancement in the Bando system. The pragmatics of physical conditioning were reinforced through day-long sessions, where practitioners were expected to endure extreme weather conditions as they learned fighting techniques. Combat skills were frequently tested during ‘war games’ and night maneuvers. Also, there were innumerable backyard and basement sessions with Maung Gyi, where select students were able to refine their skills under his careful scrutiny.

Amazingly, Maung Gyi imparted the knowledge of Bando’s nine animal systems with his students. Practitioners learned the power and aggression of the Bull, Boar, and Tiger Styles. Stealth and flexibility were engendered in many who devoted themselves to learning the Panther, Python, and Eagle Styles. As well, there was the poison and precision of the Cobra, Viper, and Scorpion Styles. With the combined talents of an Animist sage and Shaman adept, Dr. Gyi embodied each of the animals as he shared the secrets of these Burmese fighting traditions.

Dr. Gyi has formally retired as chief instructor of the ABA as of 2005, and has pledged to preserve Oopali’s valuable legacy. He now conducts classes with a cross section of health-care professionals and martial artists, including physicians, therapists, alternative healers, and practitioners of internal martial-arts systems. Dr. Gyi focuses on physical restoration and healing; internal energy management; and spiritual fulfillment through meditation and yoga. Fasting, vegetarian diets, and non-violence are key principles to be followed by Monk System adherents–all practices that Maung Gyi has grown to embrace.

More than 40 years have passed since Maung Gyi began sharing the philosophy, principles, and practices of Bando with his students in America. He journeyed from his birthplace of Mandalay, Burma across several continents and through many phases of personal development to become a major influence on martial arts in the West. Throughout this ‘enlightened journey,’ Maung Gyi never lost perspective regarding the legacy passed down by his father, Ba Than Gyi. The elder Gyi reconstituted the ancient fighting methods and strands during the pre-World War II years in Burma, and imposed a mission on his son to continue Bando’s development.

. . . . . . No one nation or system has a monopoly on truth . . . . . .

Maung Gyi has extended this legacy of pragmatics well into the 21st Century. Moreover, Bando in America has not stagnated under his leadership. Dr. Gyi has emphasized diversity in both substance and structure within the organization that he founded during the 1960s–the American Bando Association (ABA). ABA membership has always been open and unrestrictive, reflecting the social landscape of the United States. In fact, practitioners within this organization encompass a broad range of economic, ethnic, educational, and religious backgrounds. Community service is required for promotion to the instructor level (i.e., black belt rank) and beyond in order to sensitize practitioners to social differences. To extend this ideal, ABA members are required to provide volunteer services for veterans groups, senior facilities, hospitals, and public schools.

. . . . Pride, fear, and arrogance hinder the learning process . . .

As a true educator, Maung Gyi fosters a legacy of lifelong learning. Martial arts students of all ranks are encouraged to participate in Bando seminars and to explore the methods of other martial arts styles. Often, masters from other styles have been invited to teach and to demonstrate their techniques at events sponsored by the ABA. This notion of embracing new concepts and ideas is directly linked to Maung Gyi’s childhood experiences in Burma and his scholarly pursuits during the early years in the U.S. Despite numerous accomplishments, he never rests on his laurels, but rather continues to be ‘a student’ of the martial arts.

Muang Gyi actively participates in seminars lead by other masters. It is Maung Gyi’s belief that the ‘path to harmony’ must include persons from many divergent backgrounds. He further states, that all people have important ideas to share with society, and an enlightened mind will accept useful knowledge from any source.

Physical wellness is, arguably, Maung Gyi’s most profound contribution to the Bando’s legacy and to the broader martial arts community. While fitness has always been a primary component of Bando training, greater emphasis has been placed on conditioning methods during the past several years. He has updated the ABA promotion criteria to include a rigorous fitness component that parallels those of many military systems, including the Gurkha training regimen.

He believes that the body must be supple and strong throughout life, and he continues to lead many training sessions with demonstrations of his own power, speed, and flexibility. Ironically, many students and practitioners in their 20s, 30s, and 40s are unable to match the Grandmaster’s performance.

. . . . . . At the end of the day, Dr. Maung Gyi remains a humble pragmatist of life and living, remaining true to a legacy that has guided his life . . . . .

About

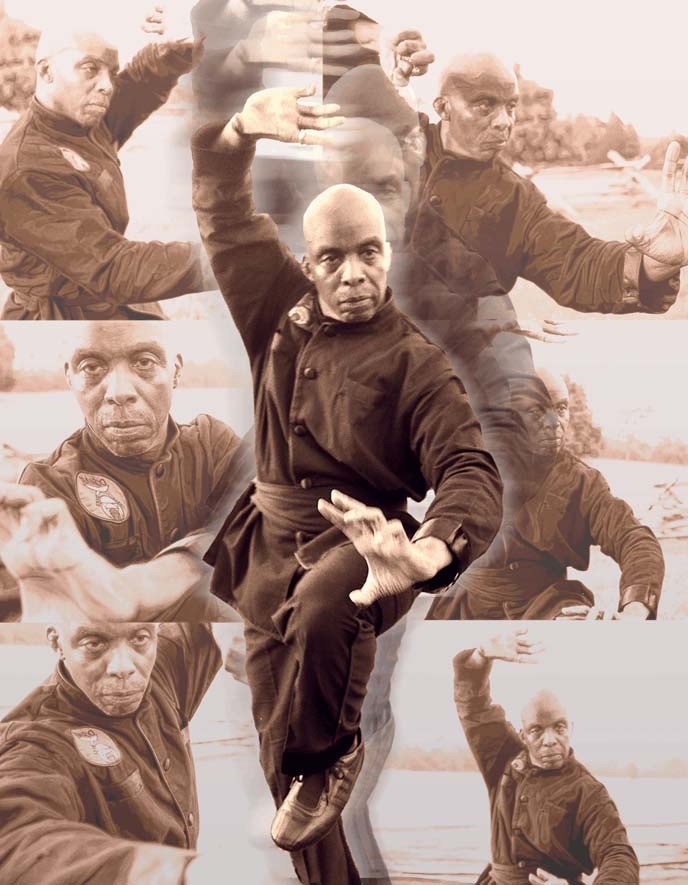

Dr. Duvon G. Winborne

Personal Background

Growing up in a large family in Baltimore, Maryland, Winborne became exposed to ideas and concepts that exceeded his chronological age during early childhood. He is the middle child of nine children and was often nudged into increasingly stronger challenges by his four older siblings. By his teen years, Winborne had been heavily influenced by the myriad accomplishments of his older siblings in the arts, music, science, and sports. His parents insisted that all nine siblings be properly socialized through robust activities in schools and the community, and that all the Winborne children attend college. Their mission was realized as the children all attended college and completed rigorous academic programs, with most attaining advanced degrees in various fields.

Following in the footsteps of his older brother of two years, Winborne attended graduate school at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Both siblings were awarded doctorates (Ph.D.) in psychology within a year of one another. Sayaji Winborne’s area of concentration was statistics, design, and computer programming, while his older brother focused on community mental health and social interventions. Over the years, the psychologist brothers collaborated on numerous projects and involved their other siblings in their professional projects—a process encouraged by their parents.

Early Martial-Arts Experiences

Sayaji Winborne began his martial-arts study as a preteen, enrolling in a karate program that was sponsored by the Baltimore County Department of Recreation in Catonsville, Maryland. The predominant systems available in the Mid-Atlantic region of the U.S. during the late 1960s were karate and judo. Winborne and his two older brothers preferred the striking methods and power of Shotokan karate, which was taught by Sensei Najib Amin (aka, Santa Jones), whom had a background in team sports and Western boxing to complement his martial-arts training. Sensei Amin emphasized the importance of physical fitness, a disciplined lifestyle, and proper diet. The powerful Amin was a vegetarian and periodically invited the Winborne brothers to his home in Catonsville for discussions on good eating habits and fitness approaches. These early influences had a lasting effect on Sayaji Winborne’s martial-arts development.

The jeet kune do training was a key phase in Winborne’s growth as a practitioner. There was an urgency to develop speed, focus, and accuracy with the kung-fu techniques. Training sessions began with extensive routines of calisthenics and always concluded with sparring competitions. It was not uncommon for Sayaji Winborne to spar against several opponents who varied in size and skill levels. Fighting techniques had to be practical, as the jeet kune do students were frequently challenged by practitioners from other styles. Sparring drills and methods were emphasized but forms were absent from Olivas’s curriculum, similar to his own experiences. The nunchuku (e.g., wooden flail) was the only weapon taught, reflecting the direct influences of Bruce Lee. Sayaji Winborne continued the kung-fu training throughout his teen years, while attending high school and college.

Transition to Bando

As mentioned earlier, Sayaji Winborne left his hometown of Baltimore, Maryland to pursue advanced training in psychology and statistics in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Also, left in Maryland were his primary training partners Sidney Grandison and Leroy Cunningham, with whom he had spent years together learning kung-fu. There were, however, new experiences that broadened Winborne’s understanding of Eastern fight systems. A graduate school classmate at the University of Michigan, Michael Sayama had studied aikido and kendo in Japan and his home state of Hawaii. Both students of psychology, Winborne and Sayama quickly developed a friendship and began training together. Sayama shared grappling methods, break-falls, rolls, staff combat, classical Japanese sword methods, and meditation approaches.

Meanwhile, Grandison and Cunningham were receiving their own expansions of martial- arts knowledge from senior Bando practitioner Robert Hill. Hill and Olivas had become acquainted through various martial-arts activities, resulting in Hill teaching some of the promising young kung-fu students in Baltimore. Grandison and Cunningham spent considerable time with Robert Hill and were consequently introduced to the Bando System. During return trips to Baltimore, Sayaji Winborne would collaborate with his old training partners and took the new information back to Michigan for cultivating his martial-arts skills.

Winborne relocated back to the Baltimore area after completing his graduate studies, taking an administrative position in Washington, D.C. He resumed his regular training with Cunningham and Grandison in kung-fu, with an increasing emphasis on the Bando System. Sayaji Winborne also enrolled in classes with noted author and martial-arts instructor Robert W. Smith. Sifu Smith held his classes in Bethesda, Maryland near D.C., where he shared with Winborne the principles and techniques of t’ai-chi, hsing-i, pa-kua, as well as the grappling method of ch’in-na.2

This period of development seemed important to Sayaji Winborne at the time. But, this view changed radically when he actually met Dr. Maung Gyi, founder and chief instructor of the American Bando Association. In that single encounter, Winborne found his “true teacher;” the kind of practitioner he had only imagined existed before meeting Mahasayaji Gyi, son of U Ba Than Gyi.3

It was as though another invitation had been offered for attending graduate school, but this time the discipline was Burmese Bando. A strong bond was formed with the Chief Instructor when Winborne began visiting the Gyi residence in Athens, Ohio. Sayaji Winborne approached the Bando learning process with the same seriousness exhibited years earlier when pursuing advanced studies in psychology and statistics.

With experiences in sparring and grappling methods, Sayaji Winborne was readily adaptable to the hard-style approaches often emphasized in Bando seminars and camps during that time period. His positions as a college professor and administrator provided enough flexibility for frequent and extended visits with Dr. Gyi in Athens. The sportive aspects of Bando were taught, including free-fighting, traditional Bama Letway, and the American version of kickboxing. Teachings of the Chief Instructor were always grounded in philosophy and expressed relative to the important principles. Many hours were spent listening to Dr. Gyi and writing copious notes on the concepts and methods being shared. Winborne even accompanied his teacher to practice sessions and competitions for the Ohio University Boxing Team, for which Dr. Gyi was the coach. Even between sparring sessions and boxing rounds, lessons were presented and Winborne was required to take careful notes. Periodically, persons would inquire about his relationship with the Chief Instructor, where upon Sayaji Winborne would humbly explain his role as a “simple scribe.” Dr. Gyi would smile approvingly and continue his instructional activities.

Relative to his own development, Sayaji Winborne is recognized for his speed and powerful striking techniques. On numerous occasions, he has demonstrated the tearing effects of Bando’s unique “cobra strike”on free-hanging paper and cardboard targets. As well, he has displayed the ability to shatter coconuts and cinder blocks with palm, fist, and elbow strikes. As Scorpion System Master, Winborne has shown the effectiveness of nerve attacks by rapidly snapping 3/4" wooden dowels with his fingers. His knowledge of weapons is extensive resulting from years of instruction from the Chief Instructor. He accompanied Dr. Gyi and other Bando practitioners to Las Vegas, Nevada for a Soldier of Fortune Convention in the mid 1990s to display khukuri methods. Sayaji Winborne effectively demonstrated the double khukuri approach by slicing free-standing coconuts in half with a single cut using either hand. Winborne is naturally ambidextrous.

Sayaji Winborne founded the Emirates Bando Association (EBA) in Abu Dhabi, UAE in 2008, and serves as the organization’s chief instructor. With over 150 students, EBA members represent more than a dozen countries throughout Western Asia and Northern Africa. Supported by Mahasayaji Gyi, Winborne’s efforts in UAE have reasonably ensured the practice and endurance of Hanthawaddy Bando in that region of the world. In 2010, Winborne and his senior students were invited by the Smithsonian Institute to present the Bando System at the prestigious 44th annual Smithsonian Folklife Festival in Washington, D. C. As the main attraction, the team of Bando practitioners demonstrated comprehensive array of fighting strategies, including Bama Letway, free-fighting, naban grappling, animal styles, long-staff methods, sword techniques, and khukuri combat. Monk System methods were also presented and the 45-minute program concluded with a coconut breaking demonstration. Filmed by the Smithsonian staff, an audience of thousands witnessed the Bando presentation at the U.S. National Mall during the July 4th celebration.

Sayaji Winborne is clear about his true accomplishment in Bando. He has learned to transform life’s adversities into positive action. Personal, career, and social challenges were reduced in importance to a mere rhythm of life—a direct result of Monk System training. Most significantly, Winborne has been able to improve the physical functioning of others and to enhance their overall well-being. This, he feels, is his real accomplishment in Bando.

About

Dr. Ameen Carter

I grew up in a small town wherein fighting was generally started by bullies and, as such, was almost a daily occurrence. Walking to school felt a lot like walking towards the boxing ring. So, sometimes the goal of the day was to ensure that you were not the first one to get hit…which meant that you had to be the one who initiated the first punch. The way we fought and won the fight, as young boys during those days, was based on who hit the other person first. As a result, one of my daily after school activities involved punching repetitively to perfect my right jab in my house and to have it ready in order to defend myself. That right jab, surprisingly, was responsible for me winning my first fight. Hence, that environment conditioned me, at an early age, to have a desire and discipline to train to fight.

As I got older, this sparked a desire to learn about martial arts. So I started reading books on karate and I became quite interested in this form of fighting. It wasn’t long before my reading turned into practicing some of the moves and techniques that were being taught in these books. I couldn’t afford to go to a karate school for formal classes but I could afford to read and practice, so this is what I did.

After some time of reading and practicing had passed, one day I decided to attempt to break a brick with a single karate chop. I took the brick, laid it down on the side of the street curb with half of it on the curb and half of it off. I got down on my knees and sized up the brick. With one single focused karate chop, I hit that brick with all the energy I could muster up and bang...with one strike that one brick turned into two neatly severed pieces. That was a pivotal moment in my life and it compelled me to want to learn more.

Shortly after the encounter with the brick I was able to join a Kempo karate class being taught by instructor Shaha Maasi. I trained with him for some time and then he introduced all of his students to a Burmese Master named Dr. U Maung Gyi, who had arrived from Burma and was teaching Bando. As a result of being in his company, we saw him throw up seven balloons in the air and burst them all in about three seconds with Cobra strikes. We also witnessed this same grandmaster fight a heavyweight champion in a legal boxing match and knocked him out in the third round with one hook punch. We heard about when Grandmaster Dr. Gyi, went to a karate school in Washington, DC and fought five black belts at one time and defeated all of them. Afterwards he invited them to join his school of which all of them accepted his invitation and eventually became his students. After this I was convinced that Bando was for me so I decided to start formally training in Bando in 1967.

Five years later I earned my First Level Black Sash. After that, however, I started to lightly delve into other systems but I always kept Bando as my base system. Actually, Dr. Gyi encouraged us to learn other systems but to always have a strong base system. Hence, my martial arts training lined up, over time, as such.

System

Instructor

Kempo

Shaha Maasi

Bando

Shaha Maasi

Bando

Grandmaster Dr. U Maung Gyi

Tai Chi Chuan

Master Chen

Tae Kwon Do

Sensei Tom Winkler

Northern Style Kung Fu

Practitioner Asad Rajab

Aikido

Sensei Maghribi

Bando

Grandmaster Dr. Duvone Winborne

I experimented with all these systems and what I found was that, while they were all effective in their own respect, they were not nearly as comprehensive as Bando. They all had many limitations when you compare them to Bando.

One of the most richest aspects of my Bando training was being taken to and participating in other systems by going to other classes. So, I was exposed to Ninjitsu and Goju and other systems, where my instructor took me to meet these instructors and their students to actually train with them in their schools. That exposure was just fantastic in terms of what I learned. Then Dr. Gyi started having two tournaments a year, one in November and one in May. He has middle style tournaments and full contact tournaments. When Bando was brought to America in the early 60s, no one had ever heard of fighting with 16 ounce boxing gloves, fighting full contact, fighting in a ring, having a doctor check your vital signs before you go into the ring, and having an ambulance on the side of the ring in case someone got injured. So Bando in America was the first martial arts system that started MMA, it was the MMA of that of that era. It was a full contact fight. Bando introduced this style of fighting to America and was later adopted by other systems and label as “kickboxing”.

In 2005 I moved to the UAE and I heard about a martial arts school teaching Bando in Abu Dhabi. I visited the school and shortly after that I began to teach weekly classes. Twelve years later this school closed and later we opened the Emirates Bando School, in Khalifa City A, which is where our current school is located. I have opened several Bando schools and taught many Bando students over the years.

I hold a Sixth Level Black Sash in Bando. My specialty is the panther system, however, I am able to teach all of the other systems in Bando under the support of Grandmaster Dr. Duvon Winborne who is the Chief Instructor of Emirates Bando.

Bando is a sport. Its main goal is to promote physical fitness, mental well- being, healthy lifestyles, and outstanding personal behavior. Ultimately, we want to produce students who will positively contribute to the growth and development of the UAE. This is what Bando is about and this is why our motto states: “Developing the best character is our focus”. This is what the teachers will teach the students and this is what we hope the students will teach other students. Our hope is that these young people will become very good citizens in this society and that they will make a major contribution to its advancement in all industries and sectors. We will do everything conceivably possible to help them maintain the kind of behavior, attitude, and personality that is exemplary and noteworthy of good, honest, responsible young men.

About

Alvis Tinnin

The Way of Victory Martial and Healing Arts School of Self-Empowerment

Alvis Tinnin is founder and Chief Instructor of The Way of Victory, Martial and Healing Arts School of Self-Empowerment. My training began with the Martial Arts and evolved to include the Healing Arts. Through training and evolution I was taught that the Martial Arts are based on the 3 H’s:

- Hurting

- Healing

- Harmony

Healing has become the focus for me and my clients; teaching, healing and harmony within and with all living things.

My journey began in 1972

- 1972-1973 Studied Shorin Ryu Karate, Redlands, California, Chief instructor George Torbett, 6th degree black belt. Rank received green belt.

- 1973-1977 Enlisted in the United States Marine Corps

- 1973-1974 Studied Ishshin Ryu Karate, San Clemente, California, Chief instructor John Bartusevics, 6th degree black belt. Rank received brown belt.

- 1974-1975 Studied Shorin Ryu Karate, Okinawa, Japan, Chief Instructor Jiro Shiroma 6th degree black belt. Rank received 1st degree black belt

- 1975-1976 Hand to hand combat, boxing, and kickboxing

- 1977 Won the Camp Pendleton Middleweight full contact Karate Championship

- 1976-1978 Studied Hung Gar Gung Fu, Los Angeles California, Chief Instructor Master Buk Sam Kong, Master of Hung Gar and Choy Lay Fut Gung Fu systems.

- 1978-1983 Enrolled as a student at North Carolina Central University. During my time on campus I taught Martial Arts on the campus and in the surrounding community.

- 1983-1996 Relocated to New Jersey and studied Bando Kickboxing. Chief Instructor Tahir Khalid. Bando is a Burmese Martial Art that is very comprehensive. Kick Boxing was initially the only aspect of Bando I studied from 1983-1996.

- 1986 Won the Bando National Middleweight Kickboxing Championship

- 1997 to present study and instruct students in Bando, Gung Fu, Min Zin, Tai Chi and Chi Gung. Current Chief Instructor, Grand Master Maung Gyi, Grand Master of the American Bando Association. My current rank is 5th level black belt in Bando.

- 1998 due to my years of intense training in external arts I began earnestly studying and practicing the Healing Arts of Tai Chi, Min Zin and Chi Gung. My Instructors in the Healing Arts were Howard Anderson (Tai Chi and Chi Gung) Stephen Chang (Chi Gung)

I continued to receive instruction and guidance in all aspects of my Martial and Healing Arts training from my current instructor Bando Grand Master Maung Gyi.

Healing Arts

In the Way of Victory we teach two primary methodologies of internal energy cultivation Chi Gung (sometimes spelled Qigong) which has a Chinese base and Min Zin which is based out of the Southeast Asian country of Burma. The internal healing exercises presented are either Chi Gung, Min Zin or a combination thereof. Below is a brief explanation of the two primary Healing modalities taught in the Way of Victory Martial and Healing Arts School of Self-Empowerment.

Chi Gung and Min Zin.

Meaning of Chi Gung

Chi-gung, which also translated as "energy work," is a system of cultivating health, vitality, and longevity. Practiced by the Chinese for thousands of years, chi-gung works with the energy found in all living things to help rid the body of the imbalances that sap our strength and give rise to disease. The simple, meditative movements and breathing exercises that are the basis of chi-gung can be practiced by anyone, regardless of age or physical fitness.

The Chinese character for Chi in Chi Gung means air or energy. Gung means discipline or skill, so Chi Gung can be described as breath or energy skill/work. Chi Gung is an internal Chinese meditative practice which uses slow graceful movements and controlled breathing techniques to promote the circulation of Chi within the human body, and enhance the practitioner's overall health. They are based on the awareness that there is a “Life Energy” (chi) flowing through our bodies which can be strengthened.

You possess the ability to tap the abundance of internal energy (called Chi in Chinese). To tap into this power one must simply initiate a daily practice and the energy will begin to expand exponentially. Energy goes where the mind directs. The more you direct the energy the more you will be able to harness it. As you learn this system to direct your flow of chi, you will be able to.

- Develop certain abilities

- Increased vitality

- Strengthened immune system

Meaning of Min Zin

The word Min Zin is a truncated term from a larger phrase, derived from the Pali and Boshan language of the ancient Shan people of southeastern Burma, Tibet and China. Min signifies king, ruler, control, regulated, Zin indicates path, way method or technique. Min Zin can be understood as techniques of generating, storing, and transmitting internal energy. Internal energy is referred to as Gha, (Burmese) Chi, (Chinese) Prana, (India) Ki (Japanese) Universal Energy (English). One basic premise of all internal energy cultivation systems is that energy goes where the mind directs.

Min Zin teaches that that the human body is an energy system and a sustained rhythmic flow of energy within the human body is necessary for good health and physical wellbeing. There are three types of breath:

- Everyday breath, which is basically unconscious one is not even aware that they are breathing.

- Regulated breath, breath that complements a physical activity like swimming or lifting weights.

- Disciplined breath, focused breathing which requires conscious inner sight and intention.

Both Chi Gung and Min Zin utilize disciplined breath.

Meaning of Mudras

Mudras are positions of the body that have some kind of influence on the energies of the body, or your mood. Primarily the hands and fingers are held in a particular position, however the whole body may be part of a mudra as well. Mudras are employed in both Chi Gung and Min Zin.

Causes of Illness and Disease

In the Way of Victory we are offering a compilation of the healing modalities of Chi Gung and Min Zin each of which have greatly benefited humanity on many levels for thousands of years. Since we are sharing a healing system it is appropriate that mention is made on the causes of illness and disease:

- Improper diet {food and drink}

- Improper rest {sleep}

- Improper use of physical effort {overuse, misuse, and abuse of the body}

- Improper thoughts and emotions {anger, fear, grief}

- Improper exposure to natural elements {cold, heat, damp etc}

- Improper interactions with diseased person/s {TB, HIV, Typhoid Cholera, etc}

- Improper contact with the jinn and other negative connections

- Improper seeds from ones ancestors {genetic defects or imbalances}

- Improper misdeeds or actions

All 9 of the causes of illnesses and diseases are within our ability to control. Some core Min Zin beliefs are:

- We cause most of our sicknesses and emotional problems

- The human body has the innate ability to heal itself

- We are responsible for our own health and happiness

The flow of energy/ life force in the human body can be regulated by, thought patterns, breath patterns and postural patterns often a combination of all three. The human body is an energy system. There are 9 major energy zones in the human body which when activated through conscious and disciplined breathing will magnify or initiate the bodies innate capacity to heal itself. A sustained rhythmic flow of energy within the human body is necessary for good health and well-being. Energy goes where the mind directs!

The 9 energy zones in the Head and Body

The energy zones also known as chakra’s in Min Zin are slightly different from that of the Indian, Tibetan and Chinese systems.

Zone-1: Top of head area this zone connects the left and right hemispheres of the brain. Activation of this zone can be very beneficial and is often referred quite appropriately as Heaven’s gate.

Zone-2: The middle of the fore head sometimes referred to as the 3rd eye. Zone 2 is your frontal lobe which governs critical thought. Activation of this zone will strengthen your critical thinking.

Zone-3: The throat. This zone is used for eating, speaking and breathing. Activation will help with all of these aspects.O

Zone-4: The Solar plexus zone is where the nerves of the liver, heart, lungs and kidney join together. Activation of this zone will strengthen all of those nerves and organs and help them regain or retain their state of health.

Zone-5: The naval. This zone is the mother provider as the naval is how we initially received sustenance from our mothers. Activation of this zone is important.

Zone-6: The perineum. This area is the root of reproduction and elimination. Activation of this zone will strengthen these natural functions physically.

Zone-7: The lumbar area. This zone physically is the weight bearing area, when you perform heavy lifting much of the weight is concentrated in the lumbar or lower back area. Activating this zone will help one to bear weight more easily mentally.

Zone-8: The Thoracic Vertebrae. Activation of this zone will strengthen the nerves around your heart, strengthening and expanding their physical capacity.

Zone-9: The Cervical Vertebrae. This is the atlas that holds the skull between spine and head. Activation of this zone will enhance breathing, digestion, heart and blood vessel function, swallowing and sneezing. Motor and sensory neurons from the midbrain and forebrain travel through the medulla. As a part of the brainstem, the medulla oblongata helps in the transferring of messages between various parts of the brain and the spinal cord. In addition the brain stem is the oldest and smallest region in the human brain. The basic ruling emotions of love, hate, fear, lust and contentment emanate from this part of the brain. Activation of this zone will help one in harnessing and/or transforming the above listed emotions.